I finished my second novel! Woohoo!

In celebration, I’m going to blab about the idea that started this whole project, which is not the same as the concept or premise – writing terms that can be as confusing as %#$@.

Once upon a time, in a small-city in Kentucky that no one has heard of, a young woman was researching for another story that she finished but has never been sold. (It did win an Honorable Mention in the WOTF contest though, so there.)

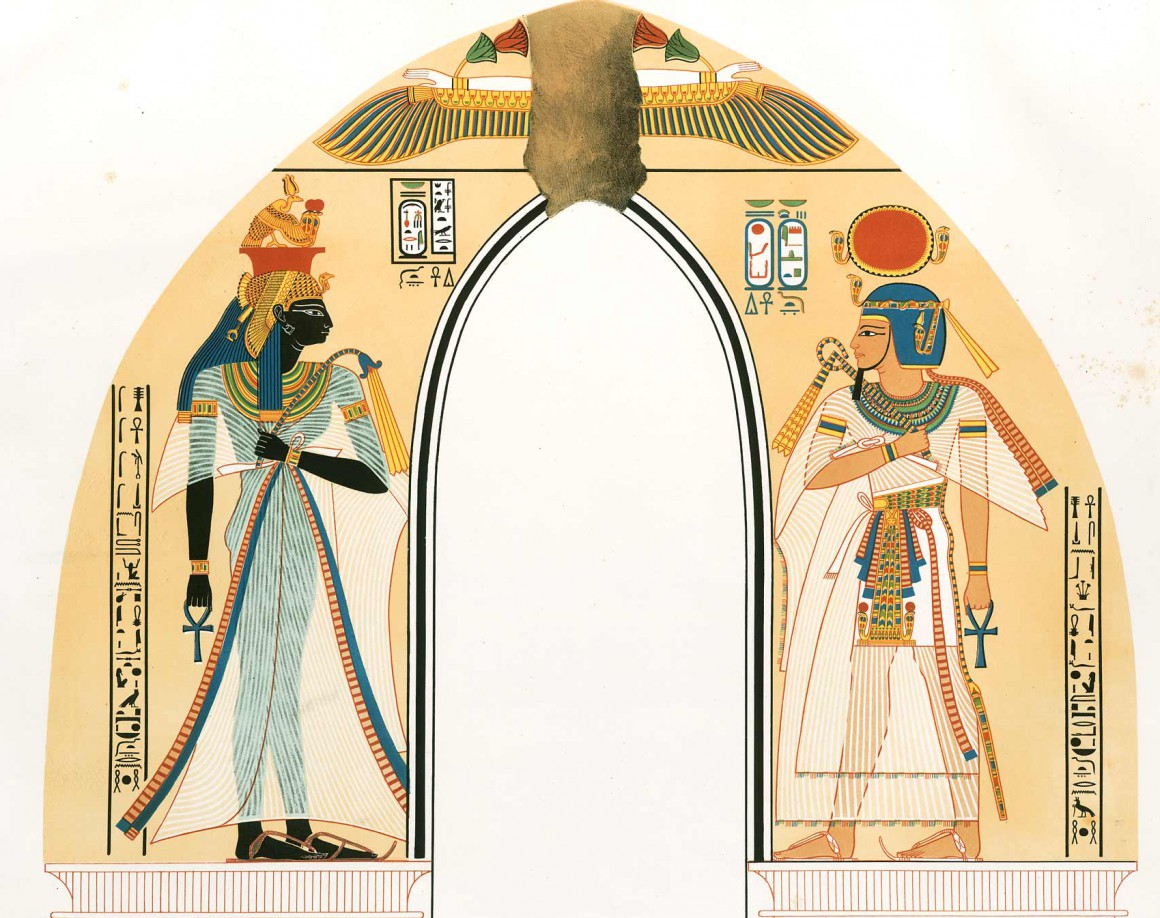

She was researching about, SURPRISE, Ancient Egypt! While doing so, she stumbled across a little dollop about the god Set in a book called ‘Egyptian Mythology’ by Geraldine Pinch. (I’m summarizing here.)

Set/Seth was red-headed. (Picture doesn’t show that, I know.)

Ancient Egyptian’s with red hair, of which the most famous example is Ramses II, were called ‘Children of Set’. Left handed red heads were especially considered of the god.

Somewhere, in that strange place in my brain, (you take two steps to the left and spin around til your sick, and you’re there,) this popped out. ‘A redhead in Ancient Egypt. Coooool.’

That’s an idea.

Simple.

Then, sometime later, probably in the shower (cause that’s when ideas happen, right?), it blossomed into this: a red head who really is Set’s child.

That’s a concept. Little fancier, got some meat, but no driving conflict element, right?

I could write a scene of a redhead wandering around in Ancient Egypt, but if she doesn’t have some sort of problem, then that’s all it is. *yawn*

Then, like magic, the premise came out of nowhere. I had a story.

An Ancient Egyptian redheaded girl, the bastard daughter of troubled War God Set, was born to save occupied Egypt, but doesn’t want to.

Set needs redemption, damn it, and Fourth’s gonna do it or die.

That’s a premise.

Why? Conflict is visible in it. HIGHLY visible in this case, because she ‘doesn’t want to’. (Might as well wave a red cape in your face.) No conflict, then no premise, then no real story.

Now, that doesn’t mean that my pacing is right or the conflict is strong enough, but hey. Who’s perfect? (My cat, that’s who. Look at that whiskery face! Nobody loves your cat like you do, Katie…)

Let’s do somebody else’s novel, a really successful one.

The Shining, Stephen King.

Idea: evil hotel.

Concept: Little boy with psychic powers lives in evil hotel.

Premise: Evil hotel wants to eat little boy with psychic powers, in order to grow stronger.

Pretty simple breakdown for a long scary book, but that’s it.

Does your story have an idea/concept/premise breakdown?

This stuff is not easy. If you can’t clearly set down a premise, then you might have an issue, either over-plotting or no real plot at all. (I hope not. Nothing more brutal to discover than that second one.)

That’s all! I’ve got a new idea bubbling, which has absolutely nothing to with Ancient Egypt. A story that arrived like the VOICE OF GOD. My favorite kind.

Go write! Here’s a really good article about idea/concept/premise. It’s free! Love free.